EECS 442: Computer Vision (Winter 2024)

Homework 2 – Convolution and Feature Detection

Instructions

This homework is due at 11:59 p.m. on Wednesday Feb 14th, 2024.

The submission includes two parts:

-

To Canvas: submit a

zipfile containing a single directory with your uniqname as the name that contains all your code and anything else asked for on the Canvas Submission Checklist. Don’t add unnecessary files or directories.- We have indicated questions where you have to do something in code in red. If gradecope asks for it, also submit your code in the report with the formatting below.

Starter code is given to you on Canvas under the “Homework 2” assignment. You can also download it here. Clean up your submission to include only the necessary files. Pay close attention to filenames for autograding purposes.

Submission Tip: Use the Tasks Checklist and Canvas Submission Checklist at the end of this homework. We also provide a script that validates the submission format here.

-

To Gradescope: submit a

pdffile as your write-up, including your answers to all the questions and key choices you made.- We have indicated questions where you have to do something in the report in green. Some coding questions also need to be included in the report.

The write-up must be an electronic version. No handwriting, including plotting questions. \(\LaTeX\) is recommended but not mandatory.

For including code, do not use screenshots. Generate a PDF using a tool like this or using this Overleaf LaTeX template. If this PDF contains only code, be sure to append it to the end of your report and match the questions carefully on Gradescope.

Python Environment

Consider referring to the Python standard library docs when you have questions about Python utilties.

We recommend you install the latest Anaconda for Python 3.12. This is a Python package manager that includes most of the modules you need for this course. We will make use of the following packages extensively in this course:

Patches

Task 1: Image Patches

A patch is a small piece of an image. Sometimes we will focus on the patches of an image instead of operating on the entire image itself.

-

(3 points) Complete the function

image_patchesinfilters.py. This should divide a grayscale image into a set of non-overlapping 16 by 16 pixel image patches. Normalize each patch to have zero mean and unit variance.Plot and put in your report three 16x16 image patches from

grace_hopper.pngloaded in grayscale. -

(2 points) Discuss in your report why you think it is good for the patches to have zero mean.

Suppose you want to measure the similarity between patches by computing the dot products between different patches to find a match. Think about how the patch values and the resulting similarity obtained by taking dot products would be affected under different lighting/illumination conditions. Say in one case a value of dark corresponds to 0 whereas bright corresponds to 1. In another scenario a value of dark corresponds to -1 whereas bright corresponds to 1. Which one would be more appropriate to measure similarity using dot products?

-

(3 points) Early work in computer vision used patches as descriptions of local image content for applications ranging from image alignment and stitching to object classification and detection.

Discuss in your report in 2-3 sentences, why the patches from the previous question would be good or bad for things like matching or recognizing an object. Consider how those patches would look like if we changed the object’s pose, scale, illumination, etc.

Image Filtering

There’s a difference between convolution and cross-correlation:

- In cross-correlation, you compute the dot product (i.e.,

np.sum(F*I[y1:y2,x1:x2])) between the kernel/filter and each window/patch in the image; - In convolution, you compute the dot product between the flipped kernel/filter and each window/patch in the image.

We’d like to insulate you from this annoying distinction, but we also don’t want to teach you the wrong stuff. So we’ll split the difference by pointing where you have to pay attention.

We’ll make this more precise in 1D: assume the input/signal \(f\) has \(N\) elements (i.e., is indexed by \(i\) for \(0 \le i < N\)) and the filter/kernel \(g\) has \(M\) elements (i.e., is indexed by \(j\) for \(0 \le j < M\)). In all cases below, you can assume zero-padding of the input/signal \(f\).

1D Cross-correlation/Filtering: The examples given in class and what most people think of when it comes to filtering. Specifically, 1D cross-correlation/filtering takes the form:

\[h[i] = \sum_{j=0}^{M-1} g[j] f[i+j],\]or each entry \(i\) is the sum of all the products between the filter at \(j\) and the input at \(i+j\) for all valid \(j\). If you want to think of doing this in terms of matrix products, you can think of this as \(\hB_i = \gB^T \fB_{i:i+M-1}\). Of the two options, this tends to be more intuitive to most people.

1D Convolution: When we do 1D convolution, on the other hand, we re-order the filter last-to-first, and then do filtering. In signal processing, this is usually reasoned about by index trickery. By definition, 1D convolution takes the form:

\[(f \ast g)[i] = \sum_{j=0}^{M-1} g[M-j-1] f[i+j],\]which is uglier since we start at 0 rather than 1. You can verify that as \(j\) goes \(0 \to (M-1)\), the new index \((M-j-1)\) goes \((M-1) \to 0\). Rather than deal with annoying indices, if you’re given a filter to apply and asked to do convolution, you can simply do the following: (1) at the start of the function and only once, compute g = g[::-1] if it’s 1D or G = G[::-1,::-1]; (2) do filtering with this flipped filter.

The reason for the fuss is that convolution is commutative (\(f \ast g = g \ast f\)) and associative (\(f \ast (g \ast h) = (f \ast g) \ast h\)). As you chain filters together, its is nice to know things like that \((a \ast b) \ast c = (c \ast a) \ast b\) for all \(a,b,c\). Cross-correlation/filtering does not satisfy these properties.

You should watch for this in three crucial places.

-

When implementing convolution in Task 2(b) in the function

convolve()infilters.py. -

When dealing with non-symmetric filters (like directional derivatives \([-1,0,1]\)). A symmetric filter like the Gaussian is unaffected by the distinction because if you flip it horizontally/vertically, it’s the same. But for asymmetric filters, you can get different results. In the case of the directional derivatives, this flips the sign. This can produce outputs that have flipped signs or give you answers to question that are nearly right but need to be multiplied by \(-1\).

Bottom-line: if you have something that’s right except for a -1, and you’re using a directional derivative, then you’ve done it with cross-correlation.

-

In a later homework where you implement a convolutional neural network. Despite their name, these networks actually do cross-correlation. Argh! It’s annoying.

Here’s my key: if you’re trying to produce a picture that looks clean and noise-free or you’re talking to someone who talks about sampling rates, “convolution” is the kind of convolution where you reverse the filter order. If you’re trying to recognize puppies or you’re talking to someone who doesn’t frequently say signal, then “convolution” is almost certainly filtering/cross-correlation.

Task 2: Convolution and Gaussian Filter

A Gaussian filter has filter values that follow the Gaussian probability distribution. Specifically, the values of the filter are

\[\begin{align*} & \text{1D kernel}: G(x) =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi\sigma^2}}\exp\left({-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}}\right) & \text{2D kernel}: G(x,y) =\frac{1}{2 \pi\sigma^2}\exp\left({-\frac{x^2+y^2}{2\sigma^2}}\right) \end{align*}\]where \(0\) is the center of the filter (in both 1D and 2D) and \(\sigma\) is a free parameter that controls how much blurring takes place. One thing that makes lots of operations fast is that applying a 2D Gaussian filter to an image can be done by applying two 1D Gaussian filters, one vertical and the other horizontal.

-

(3 points) Show in your report that a convolution by a 2D Gaussian filter is equivalent to sequentially applying a vertical and horizontal Gaussian filter.

Pick a particular filter size \(k\). From there, define a 2D Gaussian filter \(\GB \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times k}\) and two Gaussian filters \(\GB_y \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times 1}\) and \(\GB_x \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times k}\). A useful fact that you can use is that for any \(k\), any vertical filter \(\XB \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times 1}\) and any horizontal filter \(\YB \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times k}\), the convolution \(\XB \ast \YB\) is equal to \(\XB \YB\). Expanded out for \(k=3\), this just means

\[\begin{bmatrix} X_1 \\ X_2 \\ X_3 \end{bmatrix} \ast \begin{bmatrix} Y_1 & Y_2 & Y_3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} X_1 Y_1 & X_1 Y_2 & X_1 Y_3 \\ X_2 Y_1 & X_2 Y_2 & X_2 Y_3 \\ X_3 Y_1 & X_3 Y_2 & X_3 Y_3 \end{bmatrix}\]You may find it particularly useful to use the fact that \(\YB \ast \YB^T = \YB \YB^T\) and that convolution is associative. Look at individual elements. If you do this correctly, the image does not have to be involved at all.

If you have not had much experience with proofs or need a refresher, this guide will help you get started. Here is another link that will help you write readable and easy to follow solutions. But in general, the key isn’t formality, but just being precise.

-

(4 points) Complete the function

convolve()infilters.py. Be sure to implement convolution and not cross-correlation/filtering (i.e., flip the kernel as soon as you get it). For consistency purposes, please use zero-padding when implementing convolution.You can use

scipy.ndimage.convolve()to check your implementation. For zero-padding usemode=constant’`. Refer to documentation for details. For Part 3 Feature Extraction and Part 4 Blob Detection, directly use scipy’s convolution function with the same settings, ensuring zero-padding. -

(2 points) Plot the following output and put it in your report and then describe what Gaussian filtering does to the image in one sentence. Load the image

grace_hopper.pngas the input and apply a Gaussian filter that is \(3 \times 3\) with a standard deviation of \(\sigma = 0.572\). -

(3 points) Discuss in your report why it is a good idea for a smoothing filter to sum up to 1.

As an experiment to help deduce why, observe that if you sum all the values with of the Gaussian filter in (c), you should get a sum close to 1. If you are very particular about this, you can make it exactly sum to 1 by dividing all filter values by their sum. When this filter is applied to

'grace_hopper.png', what are the output intensities (min, max, range)? Now consider a Gaussian filter of size \(3 \times 3\) and standard deviation \(\sigma = 2\) (but do not force it to sum to 1 – just use the values). Calculate the sum of all filter values in this case. What happens to the output image intensities in this case? If you are trying to plot the resulting images usingmatplotlib.pyplotto compare the difference, setvmin = 0andvmax = 255to observe the difference. -

(3 points) Consider the image as a function \(I(x,y)\) and \(I: \mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\). When working on edge detection, we often pay a lot of attention to the derivatives. Denote the “derivatives”:

\[I_x(x,y)=I(x+1,y)-I(x-1,y) \approx 2 \frac{\partial I}{\partial x}(x,y)\] \[I_y(x,y)=I(x,y+1)-I(x,y-1)\approx 2 \frac{\partial I}{\partial y}(x,y)\]where \(I_x\) is the twice the derivative and thus off by a factor of \(2\). This scaling factor is not a concern since the units of the image are made up. So long as you are consistent, things are fine.

Derive in your report the convolution kernels for derivatives:

- \(k_x\in\mathbb{R}^{1\times 3}\): \(I_x=I*k_x\)

- \(k_y\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times 1}\): \(I_y=I*k_y\)

-

(3 points) Follow the detailed instructions in

filters.pyand complete the functionedge_detection()infilters.py, whose output is the gradient magnitude. -

(3 points) Use the original image and the Gaussian-filtered image as inputs respectively and use

edge_detection()to get their gradient magnitudes. Plot both outputs and put them in your report. Discuss in your report why smoothing an image before applying edge-detection is beneficial. How would the strength of the smoothing affect the final results? (2-3 sentences). -

(3 points) Bilateral Filter. Gaussian filtering blurs the image while removing the noise. There are other denoising methods that preserve image edges. Bilateral filter is one of them. Bilateral filter is not linear (as opposed to Gaussian) and can be understood as a weighted Guassian filtering. (see: Bilateral filter)

The bilateral filter is defined as:

\[I^\text{filtered}{ ( x ) }=\frac1{W_p}\sum_{x_i\in\Omega}I(x_i)f_r(\|I(x_i)-I(x)\|)g_s(\|x_i-x\|)\]and normalization term, \(W_p\), is defined as

\[W_p=\sum_{x_i\in\Omega}f_r(\|I(x_i)-I(x)\|)g_s(\|x_i-x\|)\]where \(I^{filtered}\) is the filtered image; \(I\) is the original input image to be filtered; \(x\) are the coordinates of the current pixel to be filtered; \(\Omega\) is the window centered in \(x\), so \(x_i \in \Omega\) is another pixel. \(f_r\) is the range kernel for smoothing differences in intensities (this function can be a Gaussian function); \(g_s\) is the spatial (or domain) kernel for smoothing differences in coordinates (this function can be a Gaussian function).

The weight \(W_p\) is assigned using the spatial closeness (using the spatial kernel \(g_s\) and the intensity difference (using the range kernel \(f_r\)). Consider a pixel located at \((i, j)\) that needs to be denoised in image using its neighbouring pixels and one of its neighbouring pixels is located at \((k, l)\). We assume the range and spatial kernels to be Gaussian kernels, the weight assigned for pixel to denoise the pixel \((i, j)\) is given by

\[w(i,j,k,l)=\exp\left(-\frac{(i-k)^2+(j-l)^2}{2\sigma_d^2}-\frac{\|I(i,j)-I(k,l)\|^2}{2\sigma_r^2}\right)\]After calculating the weights, normalize them:

\[I_D(i,j)=\frac{\sum_{k,l}I(k,l)w(i,j,k,l)}{\sum_{k,l}w(i,j,k,l)}\]where \(I_D\) is the denoised intensity of pixel \((i, j)\).

Follow the detailed instructions in filters.py and complete the function bilateral_filter() in filters.py. Use a bilateral filter of window size 5x5 and \(\sigma_d=3\) and \(\sigma_r=75\). Compare the results against the Gaussian filter with the same configuration(window size:5x5 and \(\sigma=3\)). Your output should be smoothed while still preserving edges. Plot the bilateral filter and Gaussian filter outputs and put them in your report.

Task 3: Sobel Operator

The Sobel operator is often used in image processing and computer vision.

-

(5 points) The Sobel filters \(S_x\) and \(S_y\) are given below and are related to a particular Gaussian kernel \(G_S\):

\[\begin{align*} ~~~~~~~~ S_x = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 2 & 0 & -2 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} ~~~~~~~~ S_y = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & -2 & -1 \end{pmatrix} ~~~~~~~~ G_S=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 1 \\ 2 & 4 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 & 1 \end{pmatrix} ~~~~~~~~ \end{align*}\]Show in your report the following result: If the input image is \(I\) and we use \(G_S\) as our Gaussian filter, taking the horizontal-derivative (i.e., \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x} I(x,y)\)) of the Gaussian-filtered image, can be approximated by applying the Sobel filter i.e., computing \(I \ast S_x\).

You should use the horizontal filter \(k_x\) that you derive previously – in particular, the horizontal derivative of the Gaussian-filtered image is \((I \ast G_S) \ast k_x\). You can take advantage of properties of convolution so that you only need to show that two filters are the same. If you do this right, you can completely ignore the image.

-

(2 points) Complete the function

sobel_operator()infilters.pywith the kernels/filters given previously. -

(2 points) Plot the following and put them in your report: \(I \ast S_x\), \(I \ast S_y\), and the gradient magnitude. with the image

'grace_hopper.png'as the input image \(I\).

Task 4: LoG Filter

The Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) operation is important in computer vision.

-

(3 points) In

filters.py, you are given two LoG filters. You are not required to show that they are LoG, but you are encouraged to know what an LoG filter looks like. Include in your report, the following: the outputs of these two LoG filters and the reasons for their difference. Discuss in your report whether these filters can detect edges. Can they detect anything else?By detected regions we mean pixels where the filter has a high absolute response.

-

(6 points) Instead of calculating a LoG, we can often approximate it with a simple Difference of Gaussians (DoG). Specifically many systems in practice compute their “Laplacian of Gaussians” is by computing \((I \ast G_{k\sigma}) - (I \ast G_{\sigma})\) where \(G_{a}\) denotes a Gaussian filter with a standard deviation of \(a\) and \(k > 1\) (but is usually close to \(1\)). If we want to compute the LoG for many scales, this can be far faster – rather than apply a large filter to get the LoG, one can get it for free by repeatedly blurring the image with little kernels.

Discuss in your report why computing \((I \ast G_{k \sigma})-(I \ast G_{\sigma})\) might successfully roughly approximate convolution by the Laplacian of Gaussian. You should include a plot or two showing filters in your report.. To help understand this, we provide a three 1D filters with 501 entries in

log1d.npz. Load these withdata = np.load('log1d.npz'). There is a LoG filter with \(\sigma = 50\) in variabledata['log50'], and Gaussian filters with \(\sigma = 50\) and \(\sigma = 53\) indata['gauss50']anddata['gauss53']respectively. You can look at these using matplotlib viaplt.plot(filter)which will show you a nice line plot. You should assume these are representative samples of filters and that things generalize to 2D.Try visualizing the following functions: two Gaussian functions with different variances, the difference between the two functions, the Laplacian of a Gaussian function. To explain why it works, remember that convolution is linear: \(A \ast C + B \ast C = (A+B) \ast C\).

Task 5: Who’s That Filter?

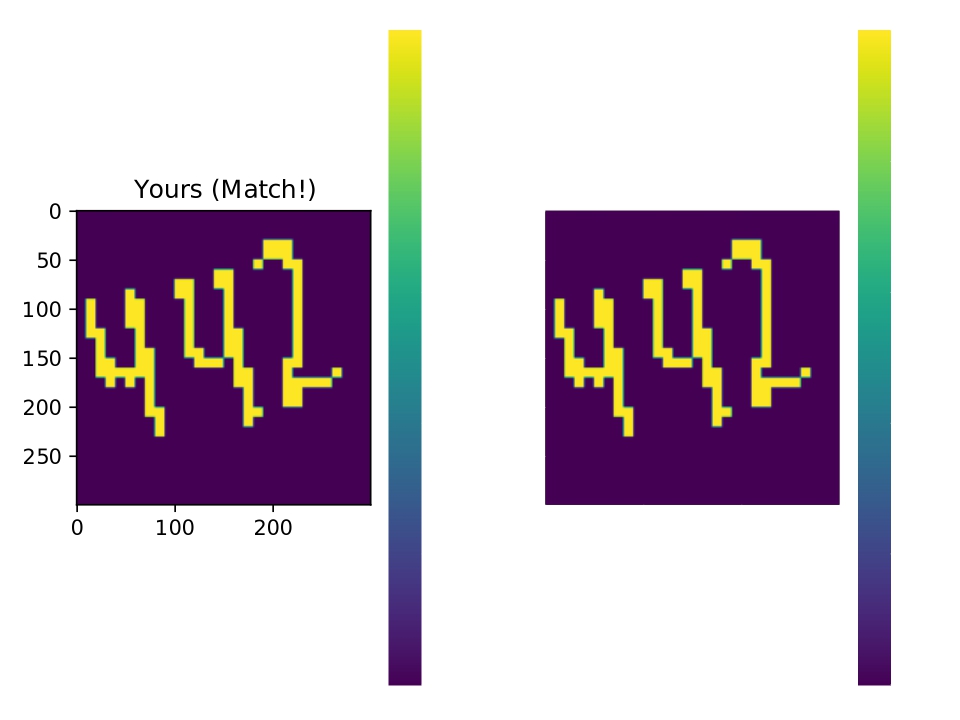

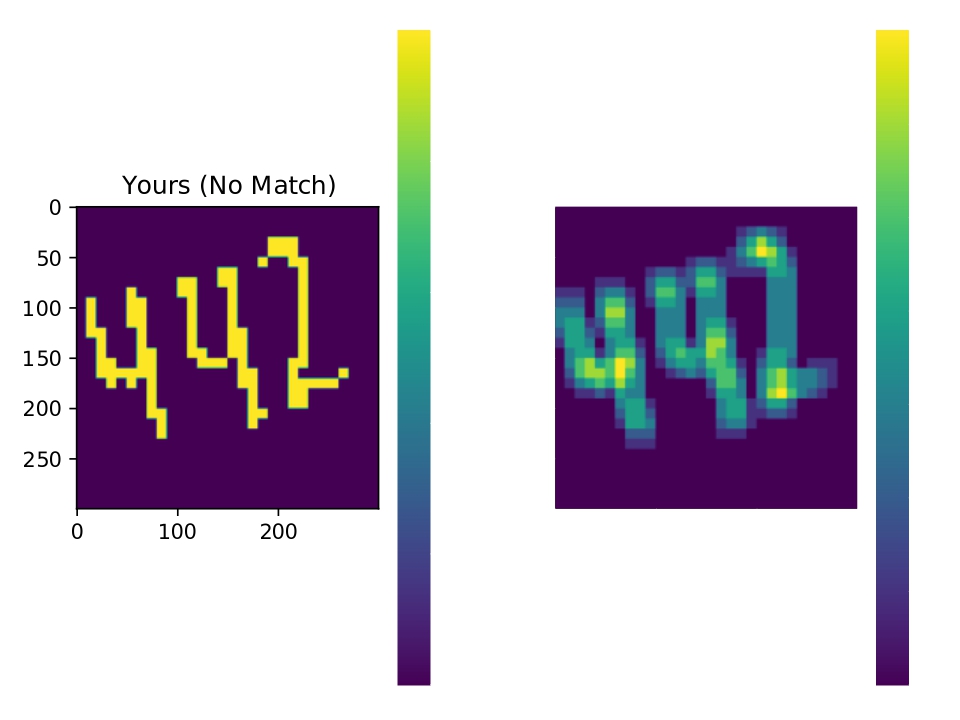

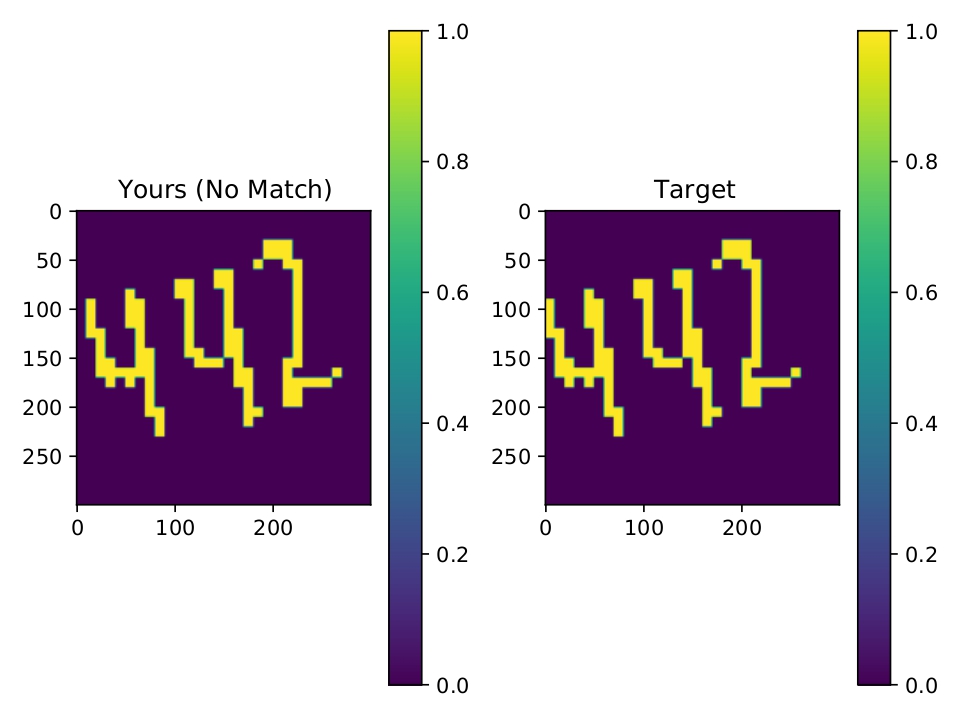

filtermon/filtermon.py. If you put the right filter in, your outputs will match the reference output.

In filtermon/, we’ve provided you with an image and its output for five different \(3\times3\) filters. The zeroth filter (the identity [[0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 0], [0, 0, 0]]) has been correctly put into the code, and so its convolution with the image will match. Update filter1 through filter4; the code will check your answers.

-

(5 points) Write out each of the four remaining filters. No need to format them prettily; something like

[[0,0,0], [0,1,0], [0,0,0]]works.Watch out that the code does convolution. If you guess the filter based on the output, remember that the filter that gets used will be horizontally and vertically flipped/reflected! All filters look similar to filters that have been shown in class (although will not match precisely).

-

(2 points) What does filter 1 do, intuitively and how does it differ from filter 2?

Feature Extraction

This question looks long, but that is only because there is a fairly large amount of walk-through and formalizing topics. The resulting solution, if done properly, is certainly under 10 lines. If you use filtering, please use scipy.ndimage.convolve() to perform convolution whenever you want to use it. Please use zero padding for consistency purposes (Set mode='constant').

While edges can be useful, corners are often more informative features as they are less common. In this section, we implement a Harris Corner Detector (see: Harris Corner Detector) to detect corners. Corners are defined as locations \((x,y)\) in the image where a small change any direction results in a large change in intensity if one considers a small window centered on \((x,y)\) (or, intuitively, one can imagine looking at the image through a tiny hole that’s centered at \((x,y)\)). This can be contrasted with edges where a large intensity change occurs in only one direction, or flat regions where moving in any direction will result in small or no intensity changes. Hence, the Harris Corner Detector considers small windows (or patches) where a small change in location leads large variation in multiple directions (hence corner detector).

Let’s consider a grayscale image where \(I(x,y)\) is the intensity value at image location \((x,y)\). We can calculate the corner score for every pixel \((i,j)\) in the image by comparing a window \(W\) centered on \((i,j)\) with that same window centered at \((i+u,j+v)\). To be specific: a window of size \(2d+1\) centered on \((i,j)\) is a the set of pixels between \(i - d\) to \(i + d\) and \(j - d\) to \(j + d\). Specifically, we will compute the sum of square differences between the two,

\[E(u,v) = \sum_{x, y \in W} [\IB(x + u, y + v) - \IB(x, y)]^2\]or, for every pixel \((x,y)\) in the window \(W\) centered at \(i,j\), how different is it from the same window, shifted over \((u,v)\). This formalizes the intuitions above:

- If moving \((u,v)\) leads to no change for all \((u,v)\), then \((x,y)\) is probably flat.

- If moving \((u,v)\) in one direction leads to a big change and adding \((u,v)\) in another direction leads to a small change in the appearance of the window, then \((x,y)\) is probably on an edge.

- If moving any \((u,v)\) leads to a big change in appearance of the window, then \((x,y)\) is a corner.

You can compute this \(E(u,v)\) for all \((u,v)\) and at all \((i,j)\).

Task 6: Corner Score

Your first task is to write a function that calculates this function for all pixels \((i,j\)) with a fixed offset (\(u,v\)) and window size \(W\). In other words, if we calculate \(\SB = {\rm cornerscore}(u,v)\), \(\SB\) is an image such that \(\SB_{ij}\) is the sum-of-squared differences between the window centered on \((i,j)\) in \(I\) and the window centered on \((i+u,j+v)\) in \(I\). The function will need to calculate this function to every location in the image. This is doable via a quadruple for-loop (for every pixel \((i,j)\), for every pixel \((x,y)\) in the window centered at \((i,j)\), compare the two). However, you can also imagine doing this by (a) offsetting the image by \((u, v)\); (b) taking the squared difference with the original image; (c) summing up the values within a window using convolution. Note: If you do this by convolution, use zero padding for offset-window values that lie outside of the image.

-

(3 points) Complete the function

corner_score()incorners.pywhich takes as input an image, offset values (\(u,v\)), and window size \(W\). The function computes the response \(E(u,v)\) for every pixel. We can look at, for instance the image of \(E(0,y)\) to see how moving down \(y\) pixels would change things and the image of \(E(x,0)\) to see how moving right \(x\) pixels would change things.You can use

np.rollfor offsetting by \(u\) and \(v\). If you look really carefully, you’ll notice that if you implement this function vianp.roll, you’ll have to watch out for whether you roll by \(u,v\) or by \(-u,-v\) if you want to calculate this precisely correct. Don’t worry about this flip ambiguity. Here’s why: in practice, if you were to use this corner score, you would try a whole set of \(u\)s and \(v\)s and aggregate the results (e.g., max, mean). In particular, for every \(u,v\), you would also try \(-u,-v\). -

(3 points) Plot and put in your report your output for for

grace_hopper.pngfor \((u,v) = \{(0, 5), (0, -5), (5, 0), (-5, 0)\}\) and window size \((5, 5)\) -

(3 points) Early work by Moravec [1980] used this function to find corners by computing \(E(u,v)\) for a range of offsets and then selecting the pixels where the corner score is high for all offsets.

Discuss in your report why checking all the \(u\)s and \(v\)s might be impractical in a few sentences.

For every single pixel \((i,j)\), you now have a way of computing how much changing by \((u,v)\) changes the appearance of a window (i.e., \(E(u,v)\) at \((i,j)\)). But in the end, we really want a single number of “cornerness” per pixel and don’t want to handle checking all the \((u,v)\) values at every single pixel \((i,j)\). You’ll implement the cornerness score invented by Harris and Stephens [1988].

Harris and Stephens recognized that if you do a Taylor series of the image, you can build an approximation of \(E(u,v)\) at a pixel \((i,j)\). Specifically, if \(\IB_x\) and \(\IB_y\) denote the image of the partial derivatives of \(\IB\) with respect to \(x\) and \(y\) (computable via \(k_x\) and \(k_y\) from above), then

\[E(u,v) \approx \sum_W \left( \IB_x^2 u^2 + 2 \IB_x \IB_y uv + \IB_y^2 v^2 \right) = [u,v] \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \sum_W \IB_x^2 & \sum_W \IB_x \IB y \\ \sum_W \IB_x \IB_y & \sum_W \IB_y^2 \end{array} \right] [u,v]^T = [u,v] \MB [u,v]^T\]This matrix \(\MB\) has all the information needed to approximate how rapidly the image content changes within a window near each pixel and you can compute \(\MB\) at every single pixel \((i,j)\) in the image. To avoid extreme notation clutter, we assume we are always talking about some fixed pixel \(i,j\), the sums are over \(x,y\) in a \(2d+1\) window \(W\) centered at \(i,j\) and any image (e.g., \(I_x\)) is assumed to be indexed by \(x,y\). But in the interest of making this explicit, we want to compute the matrix \(\MB\) at \(i,j\). The top-left and bottom-right elements of the matrix \(\MB\) for pixel \(i,j\) are:

\[\MB[0,0] = \sum_{\substack{i-d \le x \le i+d \\ j-d \le y \le j+d}} I_x(x,y)^2 ~~~~~~~~~~~~ \MB[1,1] = \sum_{\substack{i-d \le x \le i+d \\ j-d \le y \le j+d}} I_y(x,y)^2 .\]If you look carefully, you may be able to see that you can do this by convolution – with a filter that sums things up.

What does this do for our lives? We can decompose the \(\MB\) we compute at each pixel into a rotation matrix \(\RB\) and diagonal matrix \({\rm diag}([\lambda_1,\lambda_2])\) such that (specifically an eigen-decomposition):

\[\MB = \RB^{-1} {\rm diag}([\lambda_1, \lambda_2]) \RB\]where the columns of \(\RB\) tell us the directions that \(E(u,v)\) most and least rapidly changes, and \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) tell us the maximum and minimum amount it changes. In other words, if both \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) are big, then we have a corner; if only one is big, then we have an edge; if neither are big, then we are on a flat part of the image. Unfortunately, finding eigenvectors can be slow, and Harris and Stephens were doing this over 30 years ago.

Harris and Stephens had two other tricks up their sleeve. First, rather than calculate the eigenvalues directly, for a 2x2 matrix, one can compute the following score, which is a reasonable measure of what the eigenvalues are like:

\[R = \lambda_1 \lambda_2 - \alpha (\lambda_1 + \lambda_2)^2 = {\rm det}(\MB) - \alpha {\rm trace}(\MB)^2\]which is far easier since the determinants and traces of a 2x2 matrix can be calculated very easily (look this up). Pixels with large positive \(R\) are corners; pixels with large negative \(R\) are edges; and pixels with low \(R\) are flat. In practice \(\alpha\) is set to something between \(0.04\) and \(0.06\). Second, the sum that’s being done weights pixels across the window equally, when we know this can cause trouble. So instead, Harris and Stephens computed a \(\MB\) where the contributions of \(\IB_x\) and \(\IB_y\) for each pixel \((i,j)\) were weighted by a Gaussian kernel.

Task 7: Harris Corner Detector

-

(10 points) Implement this optimization by completing the function

harris_detector()incorners.py.You cannot call a library function that has already implemented the Harris Corner Detector to solve the task. You can, however, look at where Harris corners are to get a sense of whether your implementation is doing well.

-

(3 points) Generate a Harris Corner Detector score for every point in a grayscale version of

'grace_hopper.png', and plot and include in your report these scores as a heatmap.

Walkthrough

-

In your implementation, you should first figure out how to calculate \(\MB\) for all pixels just using a straight-forward sum.

You can compute it by brute force (quadruple for-loop) or convolution (just summing over a window). In general, it’s usually far easier to write a slow-and-not-particularly-clever version that does it brute force. This is often a handful of lines and requires not so much thinking. You then write a version that is convolutional and faster but requires some thought. This way, if you have a bug, you can compare with the brute-force version that you are pretty sure has no issues.

You can store \(\MB\) as a 3-channel image where, for each pixel \((i,j)\) you store \(\MB_{1,1}\) in the first channel, \(\MB_{1,2}\) in the second and \(\MB_{2,2}\) in the third. Storing \(\MB_{2,1}\) is unnecessary since it is the same as \(\MB_{1,2}\).

-

You should then figure out how to convert \(\MB\) at every pixel into \(R\) at every pixel. This requires of operations (det, trace) that have closed form expressions for 2x2 matrices that you can (and should!) look up. Additionally, these are expressions that you can do via element-wise operations (

+, *) on the image representing the elements of \(\MB\) per pixel. -

Finally, you should switch out summing over the window (by convolution or brute force) to summing over the window with a Gaussian weight and by convolution. The resulting operation will be around a small number of cryptic lines that look like magic but which are doing something sensible under the hood.

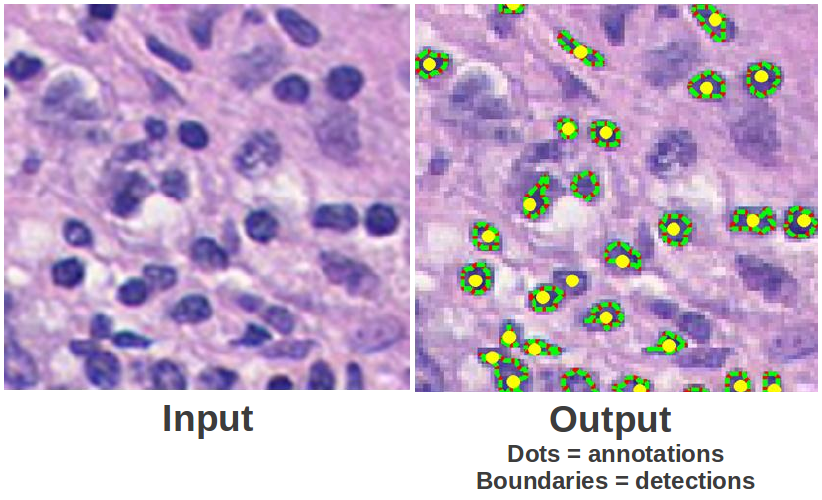

Blob Detection

One of the great benefits of computer vision is that it can greatly simplify and automate otherwise tedious tasks. For example, in some branches of biomedical research, researchers often have to count or annotate specific particles microscopic images such as the one seen below. Aside from being a very tedious task, this task can be very time consuming as well as error-prone. During this course, you will learn about several algorithms that can be used to detect, segment, or even classify cells in those settings. In this part of the assignment, you will use the DoG filters from part 2 along with a scale-space representation to count the number of cells in a microscopy images.

Note:

We have provided you with several helper functions in common.py: visualize_scale_space, visualize_maxima, and find_maxima.

The first two functions visualize the outputs for your scale space and detections, respectively. The last function detects maxima within some local neighborhood as defined by the function inputs. Those three functions are intended to help you inspect the results for different parameters with ease. The last two parts of this question require a degree of experimenting with different parameter choices, and visualizing the results of the parameters and understanding how they impact the detections is crucial to choosing finding good parameters. Use scipy.ndimage.convolve() to perform convolution whenever required. Please use reflect padding. (Set mode=reflect’`)

Task 8: Single-Scale Blob Detection

Your first task is to use DoG filters to detect blobs of a single scale.

-

(10 points) Implement the function

gaussian_filterinblob_detection.pythat takes as an input an image and the standard deviation, \(\sigma\), for a Gaussian filter and returns the Gaussian filtered image. Read inpolka.pngas a gray-scale image and find two pairs of \(\sigma\) values for a DoG such that the first set responds highly to the small circles, while the second set only responds highly the large circles. For choosing the appropriate sigma values, note that the radius and standard deviation of a Gaussian such that the Laplacian of Gaussian has maximum response are related by the following equation: \(r = \sigma \sqrt{2}\). -

(5 points) Plot and include in your report the two responses and report the parameters used to obtain each. Comment in your report on the responses in a few lines: how many maxima are you observing? are there false peaks that are getting high values?

Task 9: Cell Counting

In computer vision, we often have to choose the correct set of parameters depending on our problem space (or learn them; more on that later in the course). Your task here to to apply blob detection to find the number of cells in 4 images of your choices from the images found in the /cells folder.

This assignment is deliberately meant to be open-ended. Your detections don’t have to be perfect. You will be primarily graded on showing that you tried a few different things and your analysis of your results. You are free to use multiple scales and whatever tricks you want for counting the number of cells.

-

(4 points) Find and include in your report a set of parameters for generating the scale space and finding the maxima that allows you to accurately detect the cells in each of those images. Feel free to pre-process the images or the scale space output to improve detection. Include in your report the number of detected cells for each of the images as well.

Note: You should be able to follow the steps we gave for detecting small dots and large dots for finding maxima, plotting the scale space and visualizing maxima for your selected cells.

-

(5 points) Include in your report the visualized blob detection for each of the images and discuss the results obtained as well as any additional steps you took to improve the cell detection and counting. Include those images in your zip file under

cell_detectionsas well.

Note: The images come from a project from the Visual Geometry Group at Oxford University, and have been used in a recent research project that focuses on counting cells and other objects in images; you can check their work here.

Tasks Checklist

This section is meant to help you keep track of the many things that go in the report:

- Image Patches:

- 1.1 - 3 patches from

grace_hopper.pngandimage_patches - 1.2 - Why zero mean?

- 1.3 - Patches good or bad?

- 1.1 - 3 patches from

- Convolution and Gaussian Filter

- 2.1 - Show \(G_{xy} \equiv G_x \ast G_y\)

- 2.2 -

convolve() - 2.3 - Apply

convolve() - 2.4 - Why should smoothing filters sum to \(1\)?

- 2.5 - Derive derivative kernels

- 2.6 -

edge_detection() - 2.7 - Apply

edge_detection() - 2.8 -

bilateral_filter()and results

- Sobel Operator:

- 3.1 - Show \((I \ast G_s) \ast k_x \approx I \ast S_x\)

- 3.2 -

sobel_operator() - 3.3 - Apply

sobel_operator()

- LoG Filter:

- 4.1 - Apply LoG filters, discuss differences and detections

- 4.2 - Show \((I \ast G_{k \sigma})-(I \ast G_{\sigma}) \approx I \ast LoG\)

- Who’s That Filter?:

- 5.1 - Deduce the 4 filters

- 5.2 - Filter 1 vs Filter 2

- Corner Score:

- 6.1 -

corner_score() - 6.2 - Apply

corner_score() - 6.3 - Why is it impractical to check all \((u,v)\)

- 6.1 -

- Harris Corner Detector:

- 7.1 -

harris_detector() - 7.2 - Apply

harris_detector()

- 7.1 -

- Single-Scale Blob Detection:

- 8.1 -

gaussian_filter() - 8.2 - Apply

gaussian_filter()and comment on results

- 8.1 -

- Cell Counting:

- 9.1 - Scale space parameters and number of detected cells

- 9.2 - Include and discuss blob detection results

Canvas Submission Checklist

In the zip file you submit to Canvas, the directory named after your uniqname should include the following files:

filters.pycorners.pyblob_detection.pycommon.pyimage_patches/: directory with the detected images patches in it.gaussian_filter/: directory with filtered image and edge responses.sobel_operator/: directory with sobel filtered outputs.log_filter/: directory with LoG response outputs.feature_detection/: directory with Harris and Corner detections.polka_detections/: directory with polka detection outputs.cell_detections/: directory with cell detection outputs.bilateral/: directory with bilateral filtering outputs.